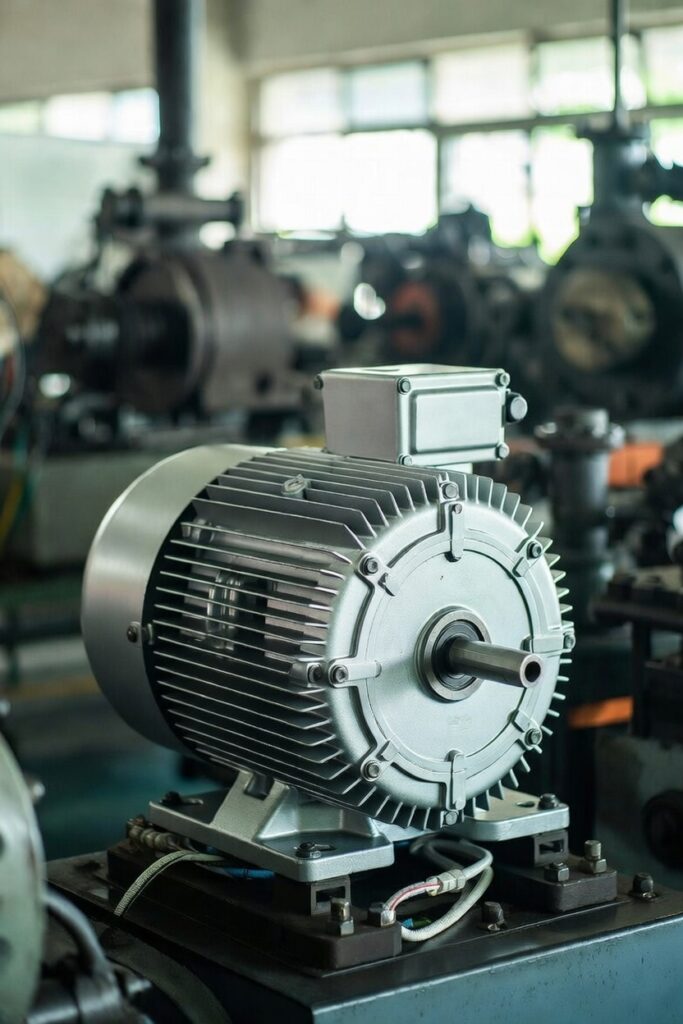

A three phase induction motor is one of the most widely used electrical machines in industrial and domestic applications due to its simple construction, ruggedness, low cost, and high reliability. It converts three phase electrical energy into mechanical energy through the principle of electromagnetic induction. The machine was Invented by Nikola Tesla in 1887.

Table of Contents

Working Principle

The three-phase induction motor operates on the principle of electromagnetic induction. When three-phase alternating current flows through the stator windings, it creates a rotating magnetic field. This field rotates at synchronous speed, determined by the formula:

Ns = 120f / P

Where Ns is synchronous speed in RPM, f is the supply frequency in Hz, and P is the number of poles.

The rotating magnetic field cuts through the rotor conductors, inducing currents in them according to Faraday’s law of electromagnetic induction. These induced currents create their own magnetic field, which interacts with the stator’s rotating field. The interaction produces a torque that causes the rotor to rotate in the same direction as the magnetic field, though at a slightly slower speed.

The Concept of Slip

The rotor never quite catches up to the synchronous speed of the rotating magnetic field. This difference is called slip, typically ranging from 2% to 5% at full load in standard motors. Slip is essential for motor operation because without it, no relative motion would exist between the rotor and magnetic field, meaning no current would be induced and no torque would be produced.

Slip (s) = (Ns – Nr) / Ns × 100%

Where Nr is the actual rotor speed.

Construction

A three-phase induction motor consists of two main components: the stator and the rotor.

The stator forms the stationary outer frame, housing three sets of windings arranged 120 degrees apart. These windings are connected either in star or delta configuration, depending on the application requirements. The stator core is made of laminated silicon steel to reduce eddy current losses.

The rotor, mounted on a shaft supported by bearings, comes in two main types. The squirrel cage rotor features aluminum or copper bars short-circuited by end rings, resembling a cage. This design is rugged, maintenance-free, and used in about 90% of all induction motors. The wound rotor, alternatively, has three-phase windings similar to the stator, with connections brought out through slip rings. This allows external resistance to be added for improved starting torque and speed control.

Types and Applications

Induction motors are classified by their rotor construction and operational characteristics. Squirrel cage motors dominate industrial applications due to their simplicity and reliability. They power pumps, fans, compressors, conveyors, and machine tools. The wound rotor motor, though less common, finds use in applications requiring high starting torque or controlled acceleration, such as cranes, hoists, and large fans.

Based on design, motors are further categorized into classes with different torque-speed characteristics. Class A motors offer normal starting torque with low slip, suitable for general-purpose applications. Class B motors provide moderate starting torque and are the most common type for pumps and fans. Class C motors deliver high starting torque for heavy loads like compressors and crushers. Class D motors produce very high starting torque with high slip, ideal for punch presses and shears.

Advantages

The widespread adoption of three-phase induction motors stems from several compelling advantages. Their construction is simple and rugged, with no brushes or commutators requiring replacement. They are highly reliable, often running for decades with minimal maintenance beyond bearing lubrication. The motors are relatively inexpensive to manufacture and operate efficiently across a wide load range. They provide smooth operation with minimal vibration and can be designed for various speeds by changing the number of poles. Their self-starting capability eliminates the need for external starting mechanisms in most applications.

Starting Methods

Despite their advantages, large induction motors draw significant current during startup, often five to seven times the full-load current. This can cause voltage drops in the supply system and mechanical stress. Several starting methods address this issue.

Direct-on-line starting, the simplest method, connects the motor directly to the supply. It’s suitable only for smaller motors where the high starting current doesn’t cause problems. Star-delta starting initially connects the windings in star configuration during startup, reducing the voltage per winding to 58% of normal, then switches to delta for normal operation. This reduces starting current to about one-third of direct-on-line values.

Auto-transformer starters use a transformer to reduce the applied voltage during starting, while soft starters employ electronic devices to gradually increase voltage. Variable frequency drives represent the most sophisticated approach, controlling both voltage and frequency to provide smooth acceleration and precise speed control.

Speed Control

Traditional induction motors run at nearly constant speed, but modern applications often demand variable speed operation. Frequency control through variable frequency drives has become the dominant method, varying both frequency and voltage to maintain optimal flux levels while changing speed. This approach offers excellent efficiency and precise control.

Other methods include pole changing, where motors are wound for multiple pole configurations allowing discrete speed steps, and rotor resistance control for wound rotor motors, though this method reduces efficiency. Voltage control provides limited speed reduction but causes significant losses and is rarely used.

Efficiency and Power Factor

Modern three-phase induction motors achieve remarkable efficiency, with premium efficiency models reaching 95% or higher. Losses occur primarily in the stator and rotor windings as heat, in the iron core due to hysteresis and eddy currents, through mechanical friction in bearings, and from windage as the rotor spins.

Power factor, the ratio of real power to apparent power, typically ranges from 0.8 to 0.9 at full load but drops significantly at light loads. Poor power factor increases current draw for a given power output, requiring larger cables and transformers. Capacitor banks are often installed to improve power factor in facilities with many motors.

Modern Developments

Recent decades have brought significant advancements to induction motor technology. High-efficiency designs minimize losses through improved materials, optimized geometries, and reduced air gaps. Premium efficiency motors, though more expensive initially, often pay for themselves through energy savings within a few years.

The integration of motors with variable frequency drives has revolutionized industrial processes, enabling precise speed and torque control while reducing energy consumption. Smart motors incorporate sensors and communication capabilities, feeding data to maintenance systems for predictive maintenance strategies that prevent unexpected failures.

Advances in materials science have produced better magnetic steels, improved insulation systems, and more efficient cooling methods. Some manufacturers now offer motors with die-cast copper rotors instead of aluminum, improving efficiency by 1-2% compared to conventional designs.

Conclusion

The three-phase induction motor represents a pinnacle of electrical engineering elegance—a device that converts electrical energy to mechanical work with remarkable efficiency, reliability, and simplicity. From small fractional horsepower units to massive motors delivering thousands of horsepower, these machines power modern civilization. As industries push toward greater efficiency and smarter manufacturing, the fundamental technology pioneered by Tesla continues to evolve, ensuring that the induction motor will remain the workhorse of industry for generations to come. Its combination of robust construction, low maintenance requirements, and adaptability to modern control systems makes it irreplaceable in the contemporary industrial landscape.