In 1924, a young French physicist named Louis de Broglie proposed one of the most revolutionary ideas in modern physics: if light could behave as both a wave and a particle, why couldn’t matter do the same?

Table of Contents

The Central Idea

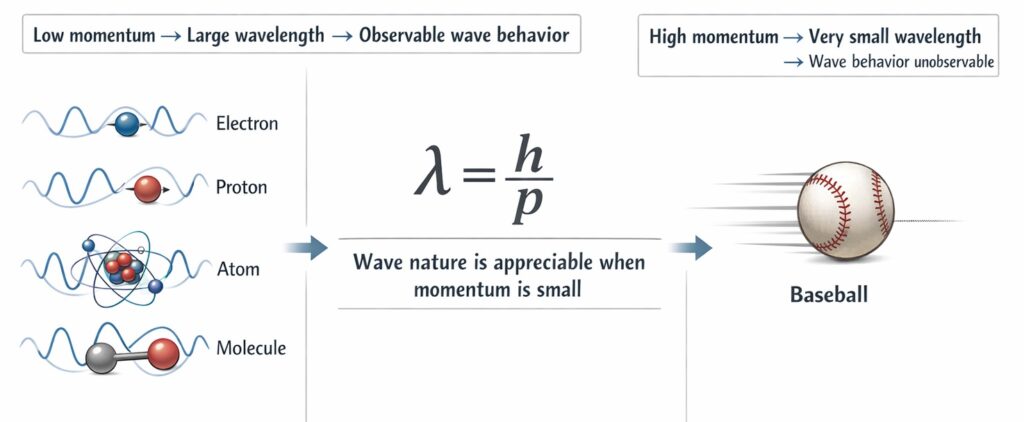

He proposed that every particle with momentum possesses a wavelength, now called the de Broglie wavelength, given by:

λ = h/p

where λ is the wavelength, h is Planck’s constant (approximately 6.626 × 10⁻³⁴ J·s), and p is the particle’s momentum (mass times velocity).

This equation suggests that the wave properties of matter become significant only at very small scales, where momentum is small.

The beauty of this relationship lies in its universality. It applies to electrons, protons, atoms, molecules, and even macroscopic objects like baseballs, though for everyday objects the wavelength becomes so vanishingly small that wave behavior is impossible to observe.

Q1. Ratio of de Broglie wavelengths of a proton and an alpha particle accelerated through the same potential difference is:

(A) \( 1 : 2 \)

(B) \( 2\sqrt{2} : 1 \)

(C) \( 2 : 1 \)

(D) \( \sqrt{6} : 1 \)

Correct Answer: (B) \( 2\sqrt{2} : 1 \)

Explanation:

The de Broglie wavelength is given by:

\[

\lambda = \frac{h}{p} = \frac{h}{\sqrt{2mK}}

\]

When a particle is accelerated through a potential difference \( V \), its kinetic energy is:

\[

K = qV

\]

Substituting this in the wavelength expression:

\[

\lambda \propto \frac{1}{\sqrt{mq}}

\]

For a proton:

- Mass \( = m \)

- Charge \( = e \)

For an alpha particle:

- Mass \( = 4m \)

- Charge \( = 2e \)

Ratio of their wavelengths:

\[

\frac{\lambda_p}{\lambda_\alpha} =

\sqrt{\frac{m_\alpha q_\alpha}{m_p q_p}} =

\sqrt{\frac{4m \cdot 2e}{m \cdot e}} =

\sqrt{8} = 2\sqrt{2}

\]

Therefore,

\( \lambda_p : \lambda_\alpha = 2\sqrt{2} : 1 \)

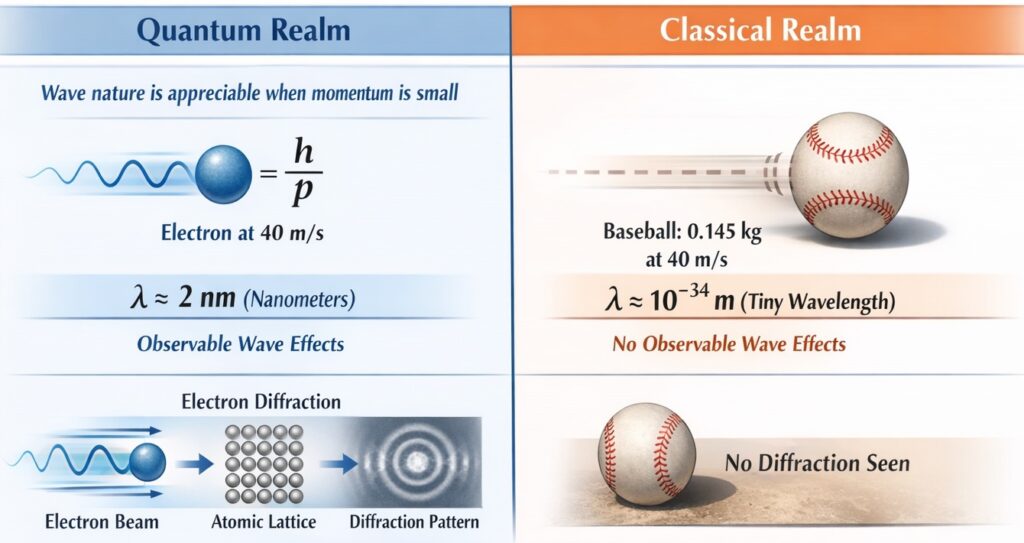

Why We Don’t See Baseballs Diffracting

To understand why quantum effects remain hidden in daily life, consider a baseball. With a mass of about 0.145 kg traveling at 40 m/s, its de Broglie wavelength is approximately 10⁻³⁴ meters, far smaller than even an atomic nucleus. At this scale, the wave nature is completely negligible. In contrast, an electron moving at similar speeds has a wavelength on the order of nanometers, comparable to atomic dimensions, making its wave properties readily observable.

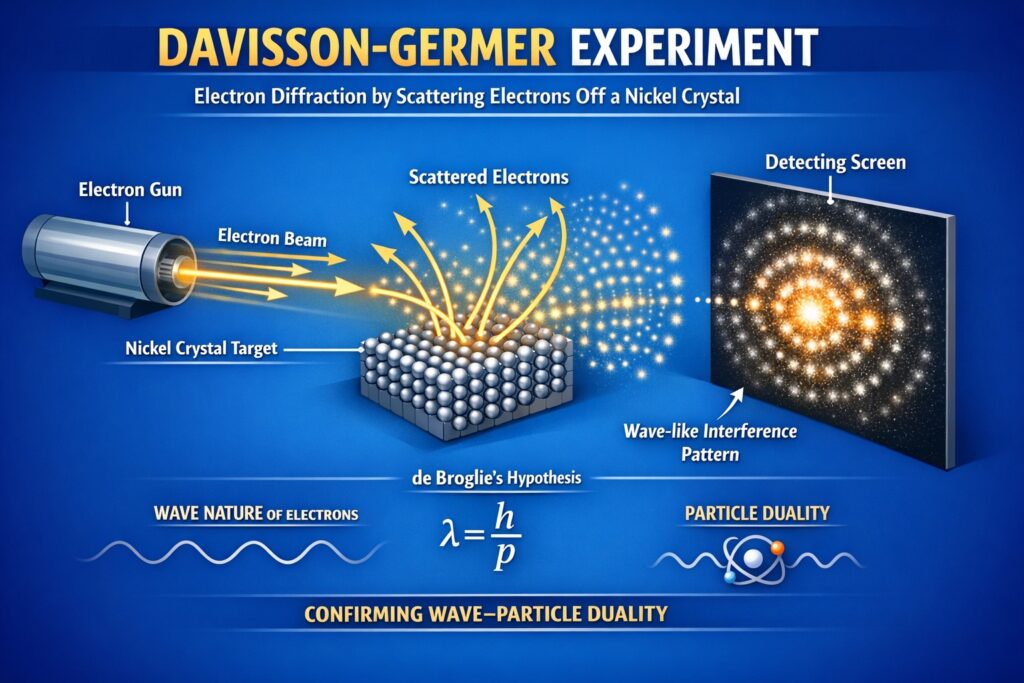

Experimental Confirmation

In 1927, Clinton Davisson and Lester Germer demonstrated electron diffraction by scattering electrons off a nickel crystal. The electrons produced an interference pattern, something only waves can do, with wavelengths matching de Broglie’s predictions precisely.

Around the same time, George Paget Thomson independently confirmed the phenomenon by passing electrons through thin metal films. The irony was not lost on the physics community: J.J. Thomson had won the Nobel Prize for showing electrons were particles, while his son George won it for showing they were waves.

Since then, matter wave behavior has been demonstrated for increasingly large particles. Neutrons, atoms, and even complex molecules like buckyballs (C₆₀) have all exhibited diffraction and interference, each confirmation extending the reach of quantum mechanics into larger scales.

Implications for Quantum Mechanics

The de Broglie wavelength isn’t merely a curious property; it’s fundamental to quantum mechanics. It provides the physical interpretation for Schrödinger’s wave function and explains why electrons in atoms occupy discrete energy levels. An electron orbiting a nucleus can only exist in states where an integer number of wavelengths fit around the orbit, much like standing waves on a vibrating string.

This wave picture also underlies the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. The act of confining a particle to a small region effectively means working with a small wavelength, which through de Broglie’s relation implies large momentum and therefore large uncertainty in momentum. The complementary nature of wave and particle properties emerges directly from this wavelength-momentum relationship.

Modern Applications

Today, the wave nature of matter isn’t just theoretical physics; it’s practical technology. Electron microscopes exploit the tiny wavelength of high-energy electrons to image structures far smaller than visible light could resolve. Neutron diffraction helps scientists determine crystal structures and study magnetic properties of materials. Atom interferometry has become a precision tool for measuring gravity and testing fundamental physics.

Perhaps most strikingly, emerging quantum technologies like quantum computers and quantum sensors rely fundamentally on the wave nature of particles. Quantum coherence, the ability of particles to exist in superposition states, is intrinsically linked to their wavelike behavior.

A Shift in Perspective

De Broglie’s insight represents more than a new equation; it embodies a profound shift in how we conceptualize reality. Matter is not simply made of tiny billiard balls, nor is it purely wavelike. Instead, nature exhibits a deeper duality that transcends classical categories. Particles have no definite wavelength in the classical sense, yet the de Broglie relation gives us a meaningful way to connect their particle properties to wave phenomena.

This duality challenges our intuition, which evolved to navigate a macroscopic world where quantum effects are negligible. Yet at the atomic scale, where the de Broglie wavelength becomes comparable to the system size, this wave-particle duality becomes the dominant reality.

Conclusion

The de Broglie wavelength elegantly bridges the gap between the particle and wave descriptions of nature, showing that both are aspects of a more complete quantum reality. Nearly a century after its proposal, it remains one of the cornerstones of quantum mechanics, essential for understanding everything from atomic structure to modern quantum technologies. It reminds us that nature’s fundamental laws often defy everyday intuition, and that the universe at its smallest scales operates according to principles far stranger and more beautiful than classical physics ever imagined.