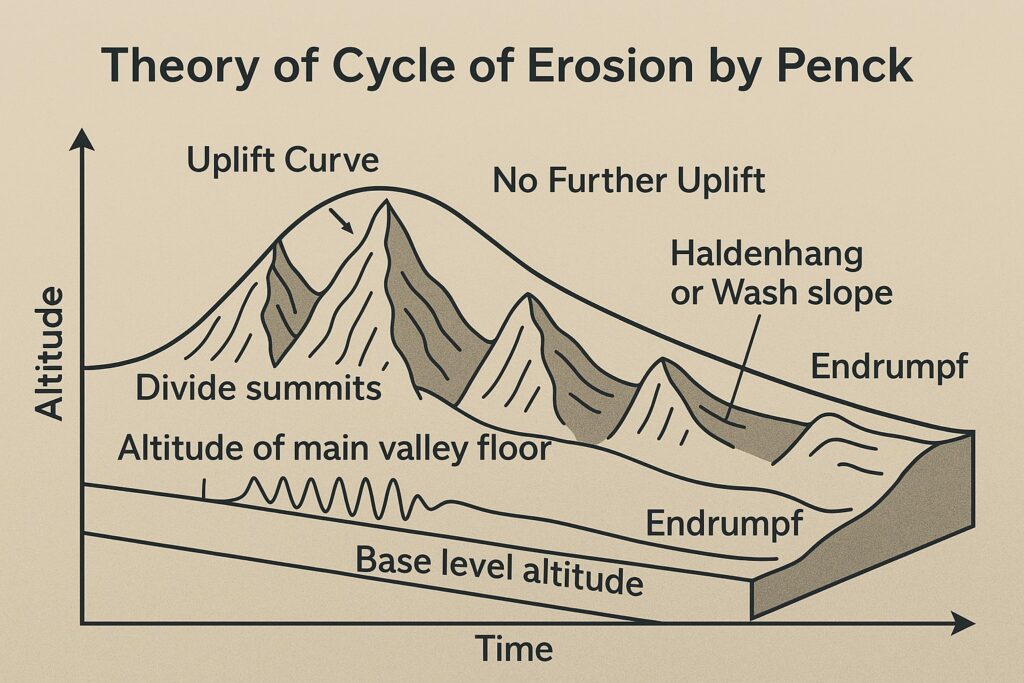

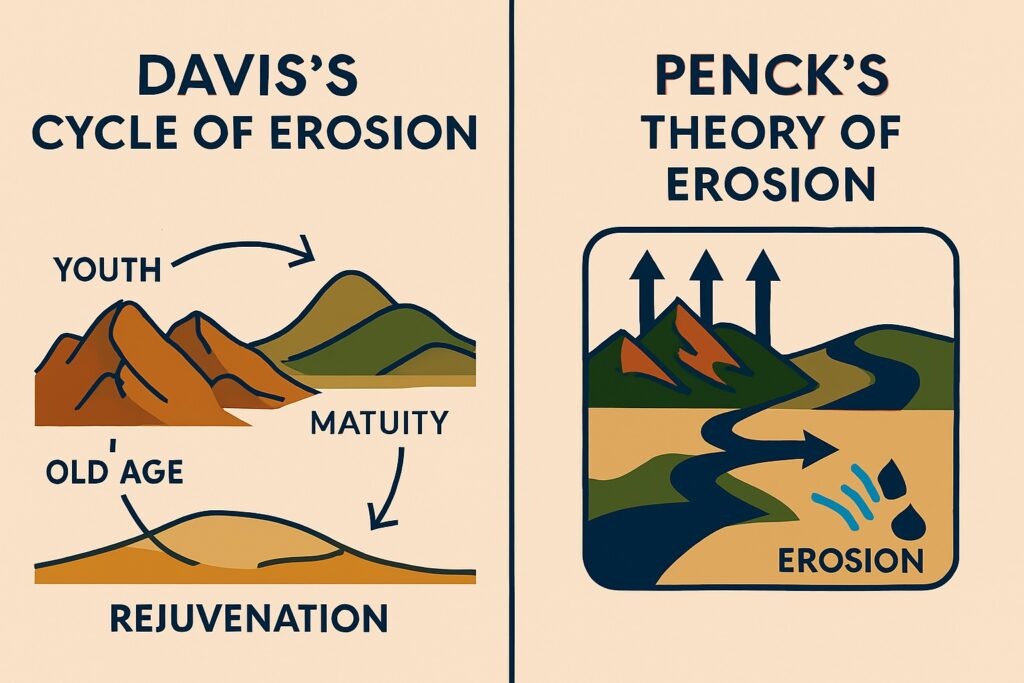

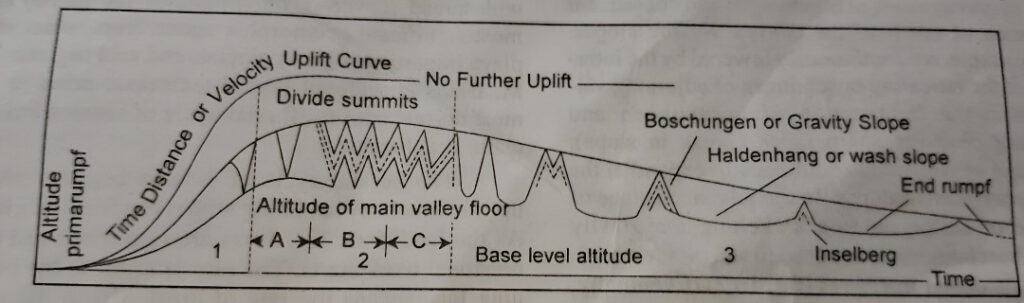

Theory of Cycle of Erosion by Penck emphasizes that uplift and erosion occur simultaneously and that the shape of landforms is determined by the rate of uplift and erosion, not solely by time. He rejected Davis’s time-dependent stages (youth, maturity, old age). The Theory of Cycle of Erosion was propounded by Walther Penck, a German geomorphologist. He proposed an alternative model to Davis’s cycle of erosion. Penck emphasized the role of tectonic uplift (endogenetic force) and rate of erosion (exogenetic force) as continuous processes that shape landforms.

Table of Contents

Basic Concept of Theory of Cycle of Erosion by Penck

Walther Penck believed that uplift and denudation (erosion) happen concurrently, not sequentially as Davis suggested. According to him, the slope form and valley development of a region are controlled by the rate of crustal uplift relative to erosion.

Penck emphasized slope development as the central feature of landscape change, and categorized landforms based on how fast the land is rising compared to how fast it is eroding.

"Geomorphology of a region is the expression of phase and rate of upliftment in relation to the rate of degradation."

Penck’s model highlights simultaneous uplift and erosion, making it more dynamic and applicable to real-world geomorphic processes.

Features of Penck’s Cycle of Erosion Model

-

- Unlike Davis’s model, Penck emphasized that uplift and erosion occur at the same time, not in sequence. This makes the model more dynamic and realistic, especially in tectonically active regions.

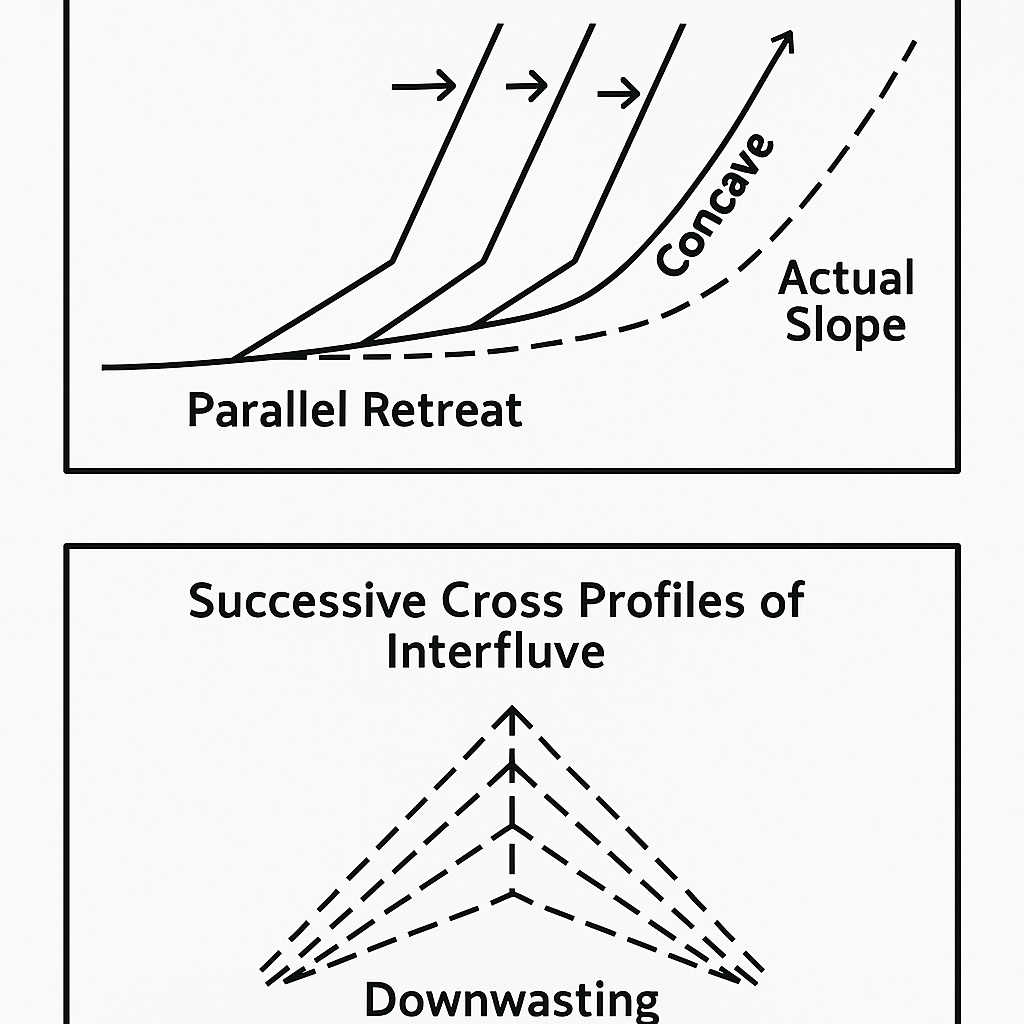

- Penck focused heavily on how slopes evolve over time.

- The shape of the slope—whether concave, convex, or straight—reflects the nature of uplift and erosion.

- He rejected the idea of fixed stages like “Youth,” “Maturity,” and “Old Age.”

- Landscapes evolve continuously, depending on the rate of uplift versus denudation.

Phases of Cycle of Erosion by Penck

Walther Penck’s Cycle of Erosion emphasizes the role of tectonic uplift and erosion occurring simultaneously. He proposed three main phases based on the relative speed of uplift and erosion, rather than a sequential process.

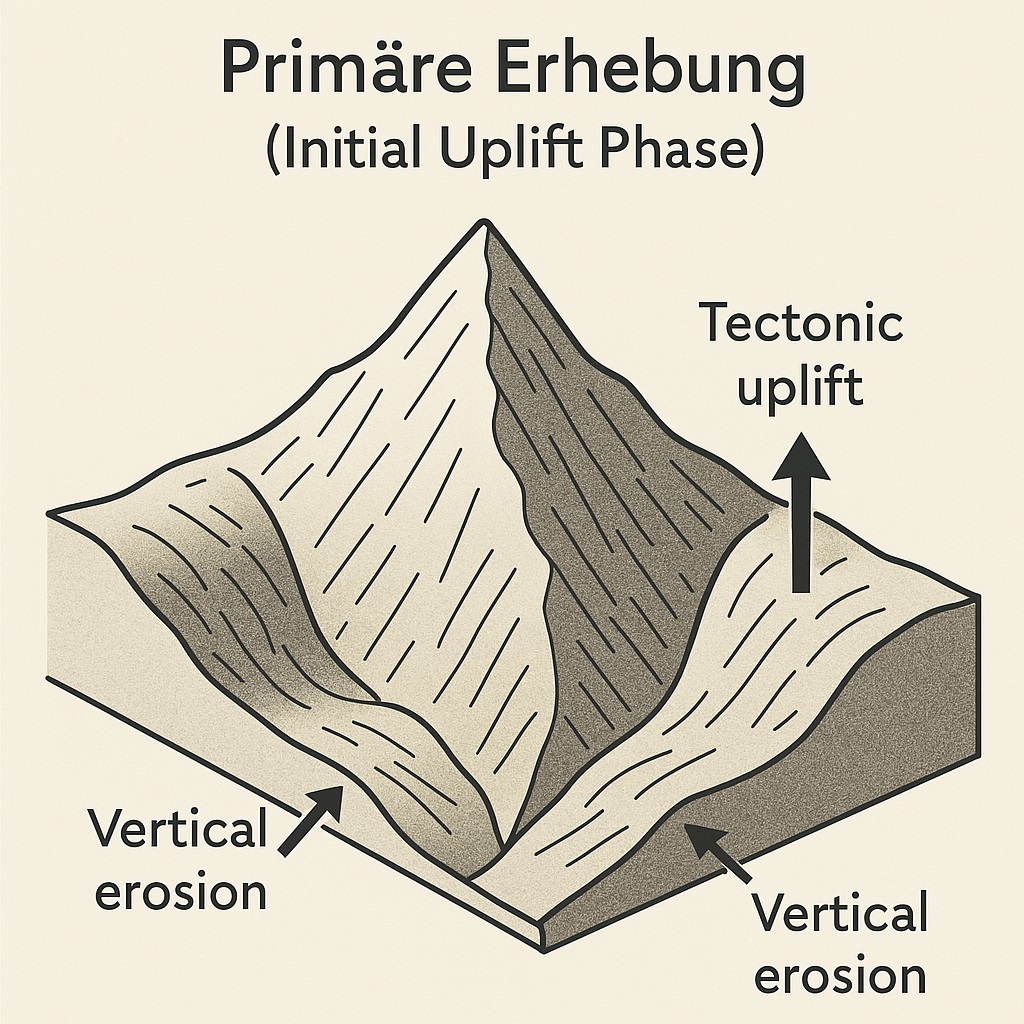

Phase 1: Initial Uplift Phase

Initial Uplift Phase, is the starting stage in Walther Penck’s theory of the cycle of erosion. In this phase, the land begins to rise due to internal tectonic forces such as orogeny (mountain-building) or volcanic activity. Unlike Davis’s model, where uplift is considered sudden and complete before erosion starts, Penck proposed that uplift and erosion occur simultaneously. As the land surface begins to rise, rivers immediately start cutting downward, leading to the development of steep, narrow V-shaped valleys.

This early erosion results in the formation of convex slopes, as the rate of uplift exceeds the rate of denudation (erosion). During this phase, the landscape is dominated by constructional processes, with elevation increasing steadily. The ongoing uplift sets the tone for future slope development and determines whether the slopes will remain convex, become straight, or turn concave in later stages. This phase marks the youthful beginning of landform evolution, with tectonic activity playing a central role.

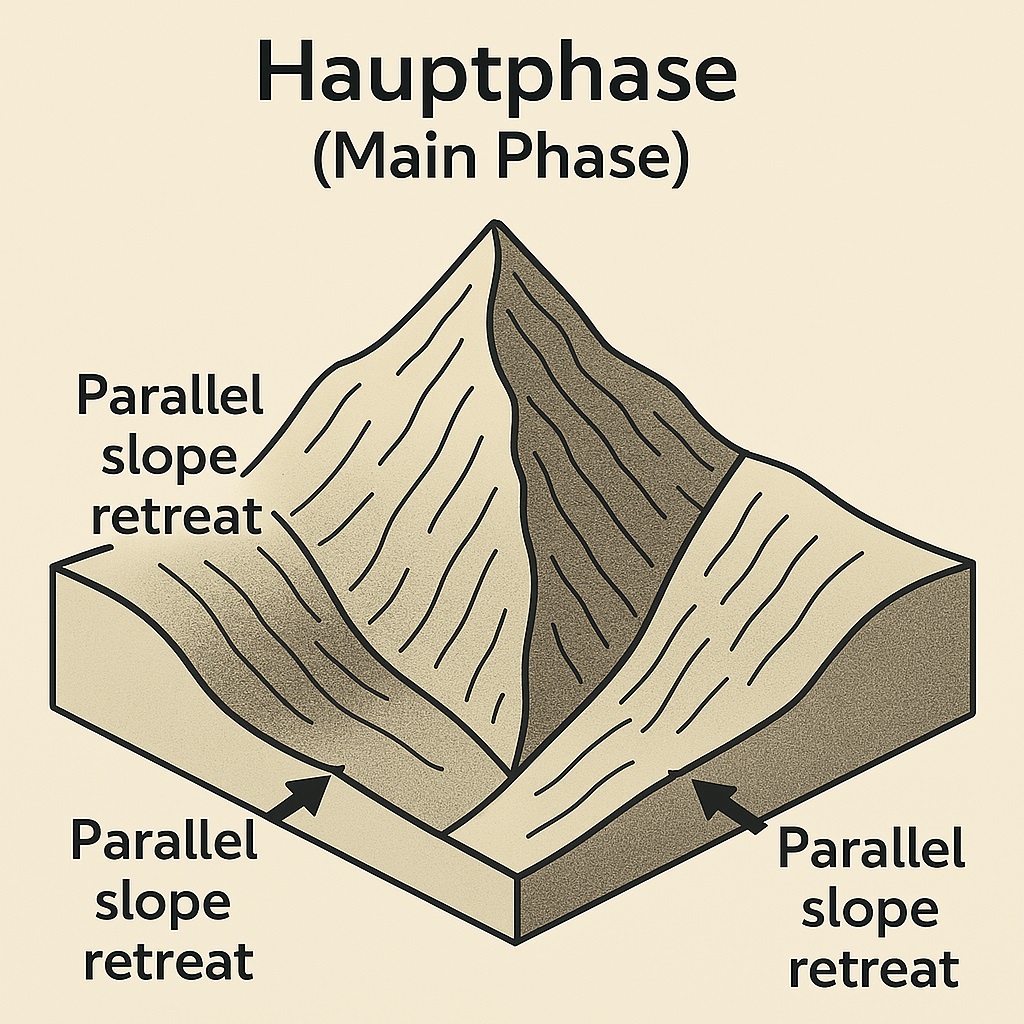

Phase 2: Main Phase

Hauptphase, meaning Main Phase, is the second and most dynamic stage in Walther Penck’s Cycle of Erosion. It follows the Initial Uplift Phase and represents the period when the interaction between tectonic uplift and erosion is most balanced and continuous. The rate of uplift slows down, allowing erosion to modify the landscape.

During the Hauptphase, the landscape experiences active slope development. The slopes, which were convex in the initial phase, begin to evolve depending on the rate of tectonic uplift relative to the rate of erosion. If the rate of uplift remains high, slopes stay steep and convex; if the uplift is steady and matches erosion, slopes become straight; and if uplift slows down, erosion begins to dominate, leading to concave slopes.

The Hauptphase is marked by the most intense geomorphic activity. River valleys deepen and widen, slopes retreat parallel to themselves, and landforms begin to take more recognizable, stable forms. Unlike Davis, who saw slope angles decrease with time, Penck observed that slopes can maintain their steepness as they retreat backward if uplift continues.

Phase 3: Final Phase

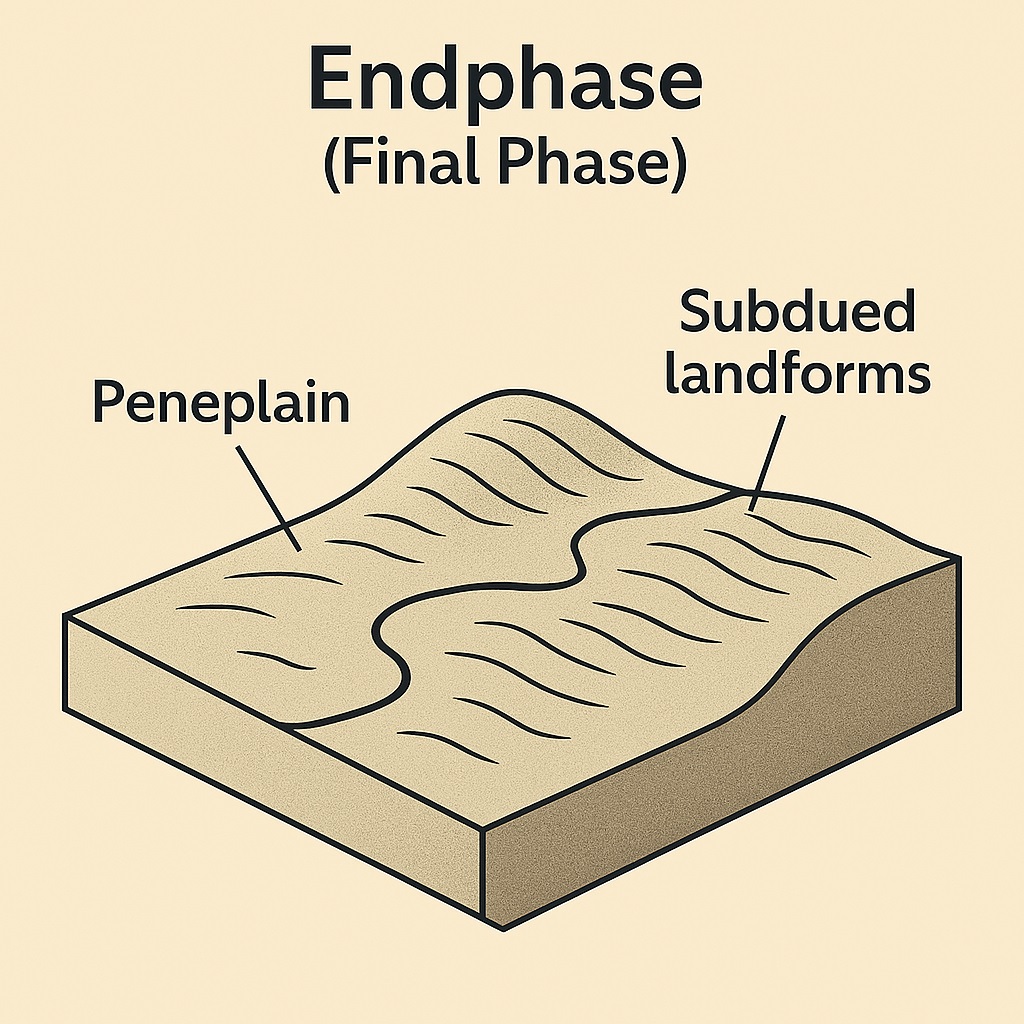

Endphase, or Final Phase, is the concluding stage in Walther Penck’s Cycle of Erosion, following the Hauptphase (Main Phase). In this phase, the rate of tectonic uplift slows down or stops entirely, and erosional processes begin to dominate the landscape.

As uplift declines, the terrain no longer receives fresh elevation, and the energy available for vertical erosion (like valley deepening) reduces. Consequently, slopes become gentler and more concave, and the overall relief of the land decreases. This leads to widespread slope retreat and surface leveling. Rivers stop incising vertically and begin to meander and widen their valleys, contributing to the formation of broad, low-relief surfaces.

The Endphase is associated with the gradual development of a peneplain—a nearly flat, featureless plain formed due to long-term erosion in the absence of significant uplift. Unlike Davis’s model, where the peneplain is seen as a stage reached after a fixed time, Penck’s peneplain forms as a natural outcome of slowing or halted tectonic activity combined with ongoing denudation.

In summary, the Endphase represents the mature and worn-down landscape, shaped mainly by erosion with minimal tectonic interference. Slopes become subdued, valleys broaden, and the land tends toward equilibrium—marking the end of the geomorphic evolution in Penck’s model.

Features of Final Phase:

-

- Uplift ceases, and erosion dominates the landscape evolution.

- Landforms become subdued, eventually resulting in a peneplain (low-relief surface).

- Rivers meander as the landscape stabilizes.

Types of Uplift

Penck categorized landscape evolution into three types based on uplift rate:

- Accelerating uplift → Convex slopes

- Uniform uplift → Straight slopes

- Decelerating uplift → Concave slopes

Evaluation of Penck’s Model

Walther Penck’s Cycle of Erosion was a significant departure from the prevailing Davisian model and, despite its complexities and initial misunderstandings, offered valuable insights into geomorphology. Unlike Davis’s stage-based and time-sequenced theory, Penck proposed a model where landforms evolve through a continuous interaction between tectonic uplift and erosion. His approach was more dynamic and better aligned with modern geological understanding, particularly in the context of plate tectonics and active mountain-building processes.

Strengths of Penck’s Cycle of Erosion:

- Emphasis on Concurrent Uplift and Erosion:

Penck’s most influential idea was that uplift and erosion happen simultaneously, rather than one after the other. This concept challenged Davis’s assumption that erosion only begins after uplift is complete. Penck’s approach reflects the modern understanding that landscapes are constantly being shaped by the interaction of rising land and the forces that wear it down. - Dynamic Approach to Landscape Evolution:

Penck’s theory is inherently process-oriented. It focuses on the rate of change rather than fixed stages. This allows for a more flexible and realistic interpretation of landform development, where varying degrees of tectonic activity and denudation operate together to shape the Earth’s surface. - Explanation of Slope Forms:

One of Penck’s key contributions was linking slope shapes—convex, straight, or concave—to the balance between uplift and erosion. This gave geomorphologists a practical framework to interpret slope profiles in the field and introduced the important concept of slope replacement, where lower, gentler slopes gradually expand at the expense of upper, steeper ones. - Polycyclic Nature of Landforms:

Penck acknowledged that landscapes often go through multiple cycles or phases of development due to recurring uplift or rejuvenation. This was a major improvement over Davis’s single-cycle model and allowed for a more accurate understanding of complex terrains with evidence of repeated erosional episodes. - Focus on Endogenic Processes:

While Davis emphasized external forces like weathering and erosion, Penck brought tectonic uplift to the forefront. He showed that endogenic forces play a central role in shaping relief and landscape evolution, especially in mountainous or tectonically active regions. - Applicability to Tectonically Active Areas:

Penck’s model is particularly relevant to areas undergoing continuous uplift, such as the Himalayas or the Andes. His ideas are better suited to explain the simultaneous development of steep slopes, active river incision, and high-relief features in such dynamic environments.

Weaknesses and Criticisms of Penck’s Cycle of Erosion:

- Complexity and Obscure Language:

Penck’s original writings, published in German, were dense and filled with technical terms that made them difficult to interpret. His choice of less familiar terminology—such as Entwickelung for development stages or Primärrumpf and Endrumpf for landscape surfaces—created confusion, particularly among English-speaking scholars. - Untimely Death:

Penck died young and was unable to further elaborate or clarify his theory. As a result, many of his ideas were left underdeveloped, and important nuances in his work remained ambiguous. - Critique by W.M. Davis:

William Morris Davis, a dominant figure in geomorphology, publicly criticized Penck’s work. Unfortunately, Davis’s critiques were often based on misunderstandings and flawed translations, but they still significantly influenced how Penck’s theory was received, especially in the English-speaking world. - Difficulty in Empirical Verification:

While conceptually appealing, Penck’s theory is hard to validate in practice. Measuring and comparing exact rates of uplift and erosion over geological timescales is challenging, and replicating his theoretical slope forms in the field is often not straightforward. - Limited Emphasis on Climate and Lithology:

Although Penck acknowledged that factors like climate and rock type influence erosion, they were not central to his model. Critics argue that these variables—especially climate—play a much greater role in shaping landscapes than Penck allowed for. - Ambiguity Around Parallel Slope Retreat:

Penck is frequently associated with the idea of “parallel retreat,” where slopes maintain their angle while shifting backward. However, there is ongoing debate about whether Penck truly advocated for this concept or emphasized slope replacement instead. This lack of clarity has led to further misunderstanding of his model.

Conclusion

Despite its initial challenges in reception and interpretation, Penck’s Cycle of Erosion—or Morphological Analysis—stands as a sophisticated and innovative contribution to geomorphology. It offered a powerful alternative to the Davisian model by highlighting the simultaneous nature of uplift and erosion and introducing a more dynamic understanding of landscape evolution.

While Davis’s theory provided a simple and accessible framework, Penck’s ideas offered a more nuanced and realistic perspective on the forces shaping the Earth’s surface. Today, geomorphologists recognize the value of both models. Elements of Penck’s theory—especially his focus on process rates, continuous change, and the influence of tectonics—remain deeply relevant in modern research, particularly in studies of active orogenic regions. His work laid the foundation for more integrated, process-based approaches that continue to inform our understanding of landform development.

Here's the updated HTML code with **3 MCQs** based on **Penck’s Cycle of Erosion**, in the exact format you provided: ```html